1939

There are a range of films we’ll be covering here. Some are movies I’ve seen before and am looking forward to revisiting, whether I haven’t seen them since their theatrical release like Amadeus or Titanic or maybe considered rewatching them yet again just recently like Return of the King. Some I knew nothing about, like Cimarron or The Broadway Melody. Two are true classics I might try to weasel out of rewatching ’cause they’re rough rides. And some are films generally agreed to be classics that I’ve never seen, in whole or possibly even in part. Which brings us to our final entry for the 30s.

The Joint Champion

The First Blockbuster. A movie so big that every mention of “Highest grossing film of all time” for the next 60 years, minimum, came with the caveat “Unless you adjust for inflation, in which case it’s still Gone With the Wind.” So here I go, trying to appraise arguably the biggest movie of the 20th century from the perspective of the 21st.

Allow me, if I may, to discuss a display at the American Museum of National History in New York.

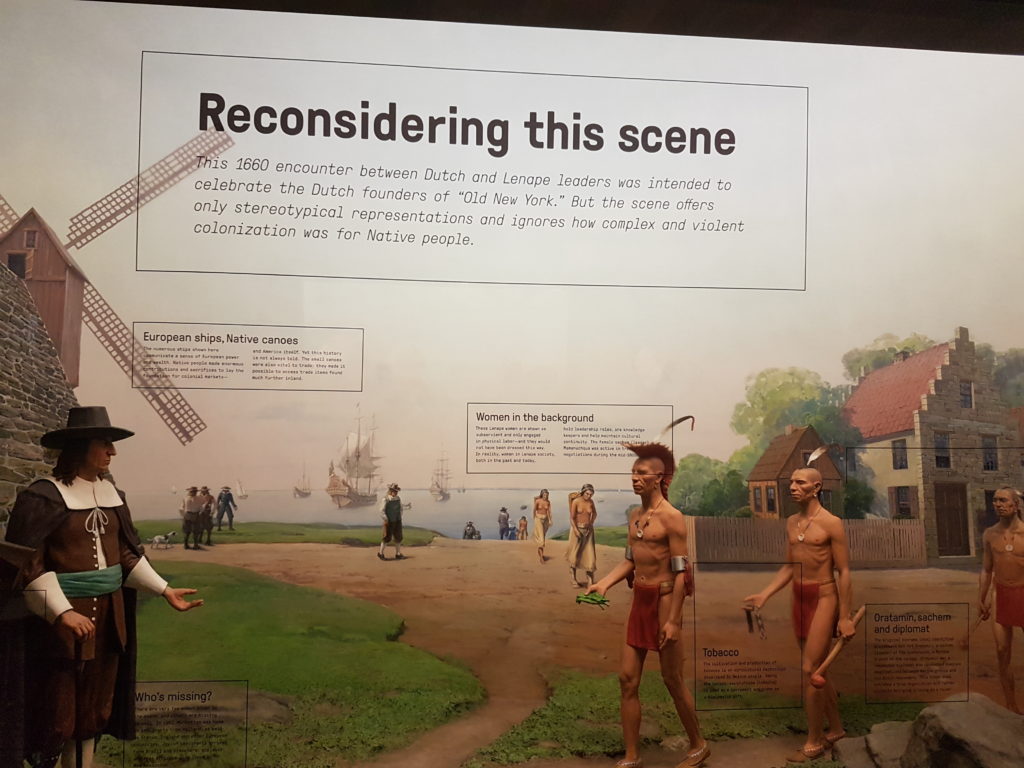

This diorama of Dutch and Lenape leaders meeting is horribly dated, incredibly inaccurate, and not just a little racist. But instead of just throwing it all in the dumpster and replacing it with taxidermized marmosets or something they covered it with these captions, explaining every single inaccuracy, from the native’s outfits and smaller ships to the lack of free Africans among the settlers. They turned this display into a testament to how wrong Americans have been viewing their own history all these years, and it’s very effective.

Gone With the Wind is a very well made movie: the performances are strong (if, like most 1930s acting, a little overwrought), the cinematography is impressive, it’s a lavish spectacle of a movie, and it’s not hard to see why audiences flocked to it, even before we mention that it’s the first movie on our list in full Technicolor.

But at it’s core, it’s discussing the fall of the Southern Confederate society, a society of wealth and lavish parties and, in their words, “gallantry.” The opening title crawl pitches that “Gallantry took its last bow. Here was the last ever to be seen of knights and their ladies fair, of master and slave.” To the first thing, says you, paleface, and to the others?

GOOD.

What we have here, in actuality, is a list of facets of Confederate life that deserved to be buried. Examples…

- Slavery, let’s get that one right out front, their fancy society is built on not paying for labour

- Victorian courtship rituals, where “Will you marry me” comes before “May I call you by your first name,” that is inherently messed up

- Widows being expected to just swoon around and mourn and stay home while doing it

- Thinking that a long history of cousin-marriage makes for strong bloodlines instead of turning swaths of the south into a morass of Snuffy Smiths

- White supremacy in general

- Pretty rigid patriarchy

So I’m not saying “Cancel Gone With the Wind,” because a) cancel culture isn’t real, and b) it is a very well-made movie. But it should be studied for the horrible traditions it is choosing to grieve.

Basically what I’ve done is I’ve found one part of this sprawling, four hour epic (again with an overture and an entr’acte, why) that really zeroes in on the film’s central flaw, and it’s Scarlett’s love life. She marries three times, and never for love. Her first husband she marries out of, far as I can tell, spite, and her second she marries for money, and even when she does finally end up with the dashing and charming Rhett Butler (because Clark Gable can’t not be both of those things), it’s for money as much as affection. But throughout it all, through three marriages, she’s constantly pining for this doof named Ashley, who marries his own cousin because, again, large swathes of white high society were built on inbreeding and now we have Brexit, QAnon, and Flat Earthers, just saying.

Ashley never fully loved her back, no matter what she thought. Ashley was devoted to his cousin/wife Melanie. Ashley was never Scarlett’s, but she spends the entire Civil War and years beyond yearning for him just the same, as if they did have this great lost love between them.

She’s glamourizing the relationship, ignoring the flaws underneath.

Ignoring future prospects by clinging to a fantasy past that was never what she thinks it was.

Remembering it as this ideal without seeing it as it was.

And that’s Gone With the Wind, babycakes. That’s Gone With the Wind to its core. And that blind nostalgia for a golden age that was actually pretty awful is the cancer at the heart of Red State America.

No wonder the only character I like is Rhett Butler, the one man who thought the Confederacy was a lost cause and their well-to-do world was an illusion. Also, again, because Clark Gable was charm personified.

(Also the fourth hour, in which Scarlett struggles with domestic life, is woefully anti-climactic compared to the rest of the movie.)

Here’s a Twitter thread of commentary.

And Rotten Tomatoes Says: The grandiose filmmaking is enough to get it into the top twenty, but its determination to plant itself on the wrong side of history means it only makes #19, with a score of 91% and adjusted score of 106%.

What Would Yancey Cravat Do: Can’t see Yancey siding with Confederates and slave owners, so… nothing Scarlett O’Hara would like.

Other Events in Film

Lots, actually: 1939 brought us Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and Basil Rathbone’s first Sherlock Holmes movie, but Gone With the Wind eclipsed them all.

My Personal Ranking

As of 1939, I would rank the Best Pictures thusly…

- It Happened One Night

- All Quiet on the Western Front

- Cimarron

- Gone With the Wind

- Wings

- Mutiny on the Bounty

- You Can’t Take It With You

- The Grand Hotel

- The Life of Emile Zola

- The Great Ziegfeld

- The Broadway Melody

- Cavalcade

Next time… the 40s arrive, and we have a new world war to fixate on. Hopefully just in this film blog and not in real life, who knows, things are still weird.

One thought on “Art Vs Commerce: Beginnings (20s/30s)”